"Ti stai già abituando a tornare lì?"

reflecting on having multiple homes - going and coming back again

I’m a bit behind on my writing here, as toward the end of October, I headed back to the States. Much as I would like to declare a more permanent residence in the EU at the moment – and the moment is a painful one to be an American citizen – that’s not in the cards just yet.

I’ve been back in New York doing work for wine fair season; it’s the busiest time of year in this business in the States, and I imagine most places. It doesn’t help that late October and November are essentially the only times it’s easier for northern hemisphere wine producers, at least those who actually farm and/or do the winemaking themselves, to travel. In this short period, fermentations largely quiet and are hopefully stable; for most people it’s also not quite the start of winter pruning season. That means everyone and their brother wants to come to New York during the same month. That’s sensible enough, but it does make for a bit of social over-exposure. And it also has been, obviously, election season—fodder for another piece.

This week, I had an Italian acquaintance from the little village where I live and work with my guy now, when I’m there, ask me a question: Ti stai già abituando a tornare lì? – “Are you adjusting to being back there yet?” I felt complicated; I said, “yes and no.” I am profoundly tired of living in NYC, but here there is also access to creative people and vitality that can be rather hard to find elsewhere, especially if you have a smaller-town or rural life where there’s simply fewer people. Or, you know, the people you’re around don’t work in wine or as chefs or as painters, activists, poets, if that’s all your cup of tea.

New York has been my home for the majority of my adult life. I won’t wax on about it—Joan Didion has already written this piece, and it’s largely perfect. Here she is from Slouching Toward Bethlehem: “Part of what I want to tell you is what it is like to be young in New York, how six months can become eight years with the deceptive ease of a film dissolve, for that is how those years appear to me now, in a long sequence of sentimental dissolves and old-fashioned trick shots—the Seagram Building fountains dissolve into snowflakes, I enter a revolving door at twenty and come out a good deal older, and on a different street.”

In my case it’s not eight years, it’s fourteen, and I have no idea what street I’ve come out on. Many streets in this town annoy me really badly now, to the point that I’ll avoid entire subway stops and lines to avoid them: 34th Street, Houston, Bedford, Knickerbocker, Myrtle Ave. But there are still those streets that still please me a lot, that I love to walk, especially now, in fall: 1st Ave., West 13th and 14th Streets, Bergen St., Irving Ave., Onderdonk.

And it’s not just to New York where I also come home; I’m spending more time these days in Pennsylvania where I was raised, which, twenty years after leaving, feels more than odd. It is peaceful in its way: I catch up on reading, running, cooking; I have no coffee dates; I do not meet people at bars or restaurants and mistakenly spend too much money, as one readily can do in the city. Despite these advantages of my being in a quieter place, there is always difficulty in going back to various homes, places where you’ve spent formative years, such that you have some very fond memories and some miserable ones—and it seems you never know which ones are going to sneak up and make you wince while you’re walking down the street.

Serendipitously, I also had this week a nice conversation with winemaker Rosalind Reynolds who produces Emme Wines, her California wine label. We were speaking about her project, the vineyards with which she partners in Sonoma and elsewhere, as well as various recent vintages. Reynolds strikes me as intelligent in a way I’m not – a science person, having studied biochemistry – and I have enjoyed very much her wines, Carignan and Grenache in particular. But also she is forthright and plainspoken in a way I like and that felt familiar to me; sure enough, in the course of the conversation, it emerged that Reynolds was raised in Lancaster, just one county over from mine. It is really interesting to talk to someone else raised in central PA about having found their way into artisanal, small-production wine work.

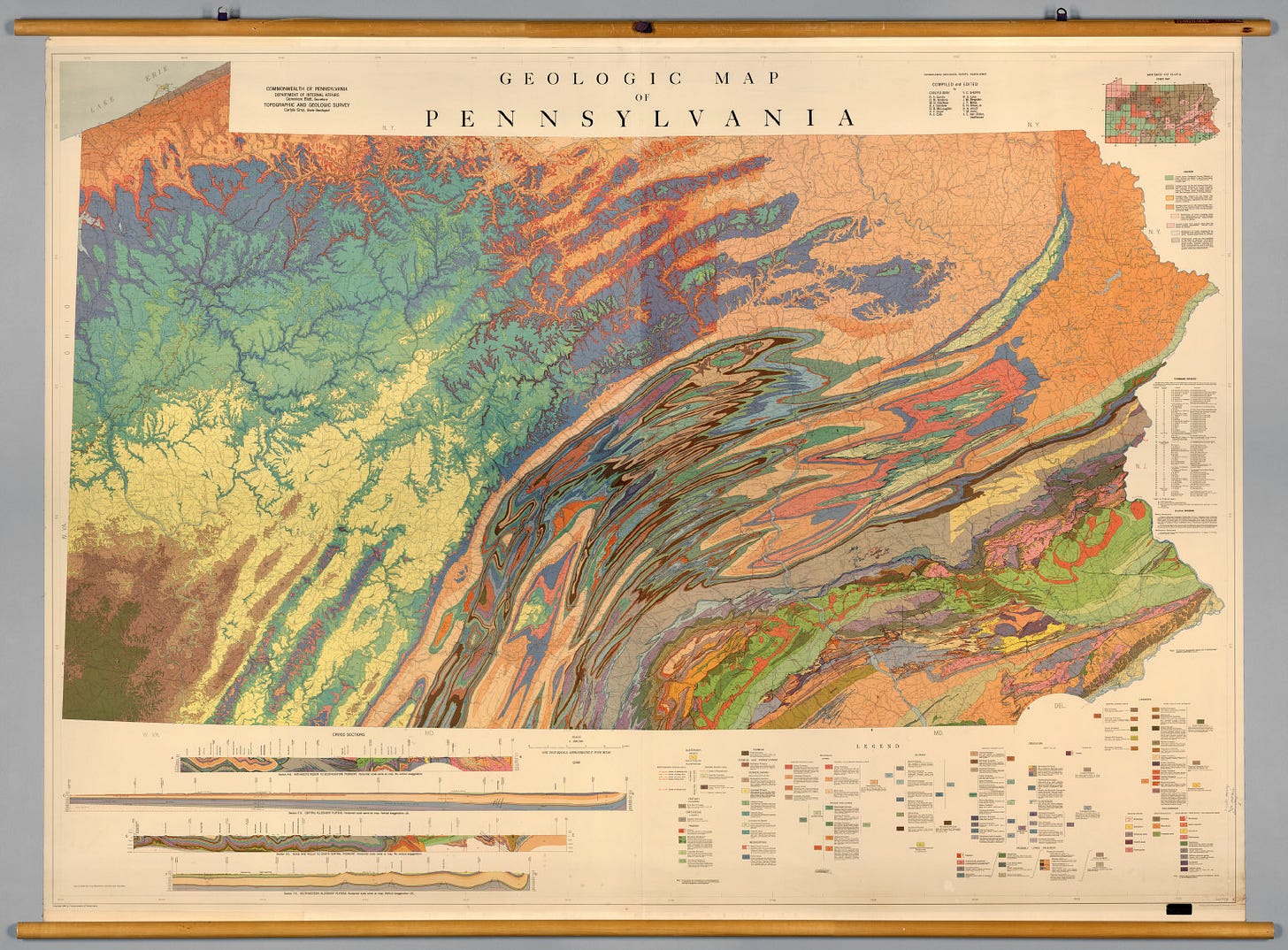

“There wasn’t much to do there when I was growing up,” Rosalind said to me about her home area, “but when I come back to visit that’s changed a bit, it’s kind of nice now.” I said the same—my small hometown now has a great non-chain bookstore, two good coffee shops, a decent brewery and a little indie cinema. Reynolds also mentioned that before she departed for Sonoma to take her full-time wine job there, she even considered putting down vines in PA. I told her I’ve looked extensively at soil maps of the region, that up in the Blue Ridge mountains there’s very interesting sandstone and old rock, things that remind me of the hillsides of Baden in southern Germany.

“Yeah,” Reynolds said, “but there’s just no infrastructure, no facilities, no one to help you get the vineyards in the ground.” In other words, there isn’t enough tradition and background in viticulture and wine production even to be able to learn from anybody, let alone easily access a press or stainless steel tanks. I said, “I know, I thought to myself: what am I going to do here, blow up a piece of one of these protected hillsides with dynamite, clear the forest and put vineyards on a slope by myself?” I’m not sure anyone’s going to let me do that, let alone whether it would be a good thing to remove even more woods in order to start doing natural wine à la Baden, in my old Pennsylvania-Dutchy home.

And yet it is strange to make wine far away from where you are from, given that you must adopt a new terroir, let it inform you as you also spend years learning parcels of plants and helping them take shape, or at least fashioning things from their fruit. Or, maybe it is just as strange to do it in an ancestral home, where the deep roots of family history and drama can creep up out of the soil to cause consternation, when all you’re trying to do is make great wine: to witness the transformative nature of fermentation, become technically proficient, make liquids that bring you and others joy.

I once had a professor muse on this business about home quite a bit; she would quote a few lines from one of her poems when discussing it: “You have to go all the way around the world to come back home,” and then a very funny image of her father in the backyard, many, many years later, having circumnavigated the globe, “and he still barbecuing!” As though thirty, forty years pass, and your old man will still just—be doing the same things he habitually did, as my dad is still talking about the same things he did when I was a kid: the resale value of cars, labor unions, birds at the birdfeeder, crazy stuff about animals he saw on TV.

When we spoke, Rosalind mentioned that in Sonoma, if you swap out the Pennsylvania dairy cows we both grew up around for vines, the landscape actually looks a lot the same. I’ve had a similar laugh at myself, now with a lot of time in the wide, open plains of the provinces of Mantua and Verona, coming to know the great river god called Po. After 20 years away from the hilly, green river valley that cradled me, I’m now in a slightly different landscape, but it’s one still dominated by a big ol’ humid river: fishermen lined up by streams in the summer, frogs and slugs at night, herons in the fields. I also think of New York again, this city a major proving ground of my life: dramatically defined by its two big rivers, the Hudson and the East. They are what I go visit when I need to be soothed here.

Maybe it is climate and topography that most shape who we are, define our longings, our color palettes and symbolism, our emotional lives. I have collected a few major homes across my life, and maybe for me, it’s these places’ rivers that will be the unifying feature—the various places themselves just spots on which to perch, big rocks in the stream along the way.