The autumn equinox was exactly one week ago; one is just beginning to feel the turn of the season. The sunset at 7 or 7:30 feels early, and I’m a little sad at the evening’s deep blue into black.

There are other signs: the persimmon tree out front is heavy with fruit, half of it green still but around half having turned bright orange. They’re not the Hachiya persimmons that you can hang to dry for a neat culinary item, but rather the more commonly seen, rounder Fuyu variety. They begin to split open on the tree as they ripen, then fall to the ground with a splat. I intend to get out on the cantina’s ladder one morning by myself and harvest a dozen or so to make a persimmon tart and also a persimmon walnut bread from a recipe from a ’90s cookbook of James Beard. I am not a regular baker, but what with all that bright orange treasure out there it’s high time I figure it out. Plus I desperately need to memorize English imperial measurement conversions to the metric system; I am already annoyed at how often I have to search online for “how many grams is three tablespoons,” and so on.

Because of this newfound need to do something about all that fruit out there, I have been reading about this tree. Here in Italy they call it kaki, after the botanical name, which I’ve noticed they do with many foreign species of plants. The best-known varieties of Diospyrus kaki are native to China, Japan, and more recently Korea. I find the habit of using botanical names here charming, since we have lots of names in English that instead come from various other cultures, descriptive habit, slang.

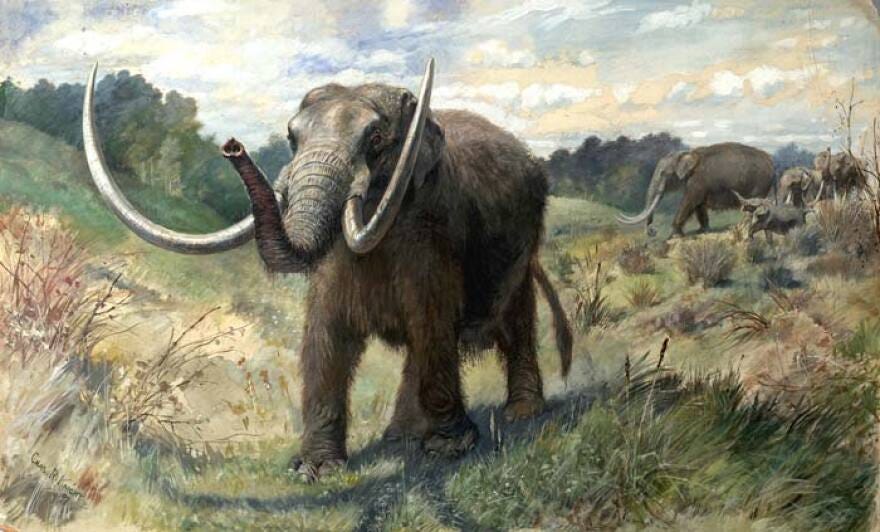

For example, I am moved by learning that the word persimmon comes from the Powhatan language, one of the Eastern Algonquin languages, from the Powhatan people traditionally living in what is now eastern, coastal Virginia. Persimmon, from pichamins, pushemins, pasimenan—all meaning ‘dried fruit.’ I learn the reason we have this word from the Powhatan is because in the east and south of the United States, we have an American native persimmon tree, usually occurring wild rather than cultivated. The fruit can be handled with cooking, drying, and baking or preserving, just like the Asian varieties. I also learn the reason we have this native American version of the persimmon is probably because of Pleistocene-era ancient elephants, trundling about the North American continent, helping the tree germinate by passing the pits through their digestive systems. Remarkable.

Raccoons in the States are known to eat persimmons, along with possum, deer, skunks, and black bears—thus a great tree to plant in your woods if you’re trying to feed the wildlife from somewhere more positive than your garbage. Raccoon is also taken from Powhatan: arahkun or arocoun, “one who scratches with his hands.” This word is so tender to me now I know what it describes, the clever, sweet, and sometimes intimidating movements of a raccoon’s extraordinary hands.

In Italian, raccoon is procióne, coming from the Greek, as often occurs in this language. Procióne, from the Greek προκύων or procyon: lesser or little dog. This name, Procyon, is given to one of two paired constellations, Canis Minor and Canis Major, the faithful dogs of Orion the Hunter. And so Italians, in order to make sense of our clever-handed raccoon, place him with their lesser Greek dog in the sky.

Kaki and ancient elephants. Powhatans and their raccoons. Greeks and the stars. If you follow the trails of plants, trees, fruit, or likewise, follow the trails of words and their origins, so much unwinds from the spool. Stories spin out farther back than you could have imagined. A weekend mental note to get outside early and bring down some fruit, before it all falls to the ground and is ruined by wasps, evolves into something deeper: the raccoons of my childhood and the people who named them, the pre-historic journey of this tree from Asia to the Americas, the English and the Italians encountering fruit and dark-eyed dogs with clever hands, of which they previously knew nothing. And now me, with a James Beard persimmon bread recipe from 1995, trying to figure out baking.

A change of season is never exactly what it seems, neither any given fruit tree in a front yard, nor the raccoon deeply interested in the trash out back. Always these things have origins from centuries or millennia ago. Often these things are tied to the stars.

My nonna used to freeze her kaki to eliminate the acrid bitterness of the less ripe ones. Here in North Carolina, we have an American persimmon on like every block. The electric company just hacked up the one in my back yard. But, lord, those American persimmons will swell my tongue and put sweaters on my teeth, no matter how ripe! Yet I still try to eat them every year. Loving this newsletter!